Steven Marsh, University of Illinois at Chicago

Numax presenta… is a singularly democratic film. I refer to its democratic form as discordant, out-of-synch with the dominant narrative concerning the ‘democracy’ under negotiation at the time of the film’s production. The film documents the dispute, subsequent strike, occupation, and self-management by a group of workers of a domestic appliance factory in the center of Barcelona between 1977 and 1979. Shot in 1979, at the initiative of the workers themselves and financed by what remained of the strike fund, the film is a performative intervention in the period of transformation of the Spanish state from dictatorship to liberal democracy. By ‘performative’ I allude to its title, the suggestion within it of a presentation; the dotted coda that hangs off the title is suggestive of both an ellipsis and of open-endedness, of unfinished business, of the inconclusive, of an uncertain future lying ahead. The film offers up a dense set of temporal relations at odds with its time; an unruly counter-current flowing surreptitiously to shape its formal diegesis; it points to a critique of traditional working practices as determining and conditioning life. Significantly, Numax presenta… is a re-presentation; it was shot after the announcement that the conflict at its heart — the collective self-operation of the factory — was over, a fact made explicit in its opening sequence. Both Numax presenta… and its 2004 sequel Veinte años no es nada are events in the sense that both films, like performative linguistic speech acts, enact what they signify (with no effort to edit out, mask or conceal the lapses and time lags involved). The event-ness of the films is key to their distinctive politics. It highlights a rupture in the everyday continuum — the norm — marked out by representational politics. Not only do the two films mark telling moments in an alternative history of democracy of the Spanish state, they are also exemplary of the formation, the forging, of a filmic site of the demos, as a voice of those habitually excluded from the discourse of democracy. In this vein I will argue here that Jordà reconfigures militant film so as to pose a challenge to conventional and enduring assumptions regarding both the cinematic and political regimes as conceived during late Francoism and the Transition.

Numax presenta… is staged in the present yet only after the event of its action. It is thereby paradoxically a documentary articulated through a fictional strategy. The film itself under workers control is a literal re-presentation that seeks therein to shape its own character, its own autonomy as demos, not only — as in the industrial dispute — from the official representatives of trade unions but also from the institutional exigencies of filmmaking. Factory workers whose daily task involved operating machines in order to shape objects extraneous to their needs and aspirations, would in this introductory declaration of intentions, give shape to their lives in the form of the film. Shape, of course, is — beyond the purview and criteria of critical discourse — a synonym for form. This chapter seeks to address questions of form; form, that is, that exceeds the limits and limitations of formalism as traditionally conceptualized in the history of cultural theory; form which is marked and conditioned by temporal-historical, social, and ideological factors. Reenactment is arguably the form of these essay films. This chapter considers thus the relation between cultural and political form at a historical juncture when both, as we will see, were in crisis. Nonetheless, the form of Numax presenta… is marked by an alternative shaping to that — the discourse — of the dominant narrative of the time ‘period’ of the production of Numax presenta…. Its historical framing, its extra-filmic reference — the Transition — notable for establishing the rarely questioned ideology of consensus, the critique of which has only recently been expressed as dissensus.

Numax presenta… is a film about organized working-class action that departs from the conventions and confines (at least those defined and practiced within the Spanish state) of most militant cinema. Jordà himself has observed that “es una película militante que rompe todos los esquemas de las películas militantes de aquel momento” [“a militant film that breaks all the molds of militant film of that moment”] (Jordà 56). In an interview with the filmmaker, Carles Guerra quotes Jordà to argue that the film’s claim to militancy is grounded in “biopolitics”:

«primero los trabajadores parten de un objetivo intentan mantener el poder obrero dentro de la fábrica, hasta que se impone una segunda reflexión. Al final, abandonamos ese simulacro de poder y vamos a la vida». A partir de este punto la gestión política pasa a ocuparse de algo más que la economía, los horarios o las condiciones laborales. Se ocupará de la vida dejando el terreno preparado para una militancia que, recordando el curso impartido por el filósofo francés Michel Foucault en los primeros meses del año1979 – justo en el momento que se filma Numax presenta…– , será de corte biopolítico.

[the workers first began with the objective of keeping workers’ power within the factory, until a second reflection took hold. In the end we abandoned that simulacrum of power and opted for life itself”. From that point on, politics becomes more significant than economics, working hours or labor conditions. Life is spent pre-paring the terrain for a militancy that, to recall French philosopher Foucault’s course offered in the first months of 1979—at the very moment that Numax presenta… was being filmed—was of a biopolitical nature]. (Guerra 52).

It is in such statements that we can see the underlying influence of Jordà’s erstwhile involvement with Autonomía, a significantly different project to that of Foucault’s thought not altogether unconnected to it — more biopolitical than disciplinary. During his years in exile in Italy Jordà had met (and planned a filmed interview with) Toni Negri, one of the ideologues of Autonomia. Negri was, of course, also influenced by biopolitics. Upon return to Barcelona Jordà came into contact with Spanish/Catalan autonomistas such as Santiago López Petit who were critical of what they termed the “authoritarian Left” (particularly the Communist Party, but also other groupings such as the LCR, who were active in the Numax occupation). Jordà had clearly traveled a long way from the time of the 1970 Lenin vivo, that he co-directed with Gianni Toti. One of the many interesting things about the sequel to Numax presenta…, Veinte años no es nada, is that we learn how the fragmentation and dispersal of the Numax collective after the end of the occupation mirrors (in some ways) that of the Lotta Continua, Potere Operaio and other Italian workerist groups who would from 1973 onwards form “Autonomia Operaia”. A rejection of traditional working class representatives as hopelessly compromised — and institutionalized — with the State apparatus (itself in crisis), a rejection of salaried work (that many of the members of the Numax collective express in the party that marks the end of the occupation and the film) and even the recourse to armed struggle by a minority element of the Italian workerists. Much of this critique of representation manifested itself (particularly in the case of Potere Operaio) in terms of formal practices. I want then to map the complex relations (noting the departures, the non-correlations) between formal filmic practices and the form of politics practiced by the workers themselves. Jordà’s earlier work as a traditional militant filmmaker at the service of the Communist Party (that of Lenin vivo [1970] and Portugallo, paese tranquillo [1969]) brings with it a change in formal practice. If form is historically marked then questions of form (political and artistic) and those of crisis are perhaps relevant to the year Numax was shot. 1977-78 witnessed unprecedented upheaval in Italy among workers and students — notably in Bologna — inspired by the extra-parliamentary left in opposition to the State, which counted on the complicity of the PCI. It also saw corresponding repression on the part of the State in collaboration with extreme right-wing paramilitaries. Likewise, the critique of capitalism and the reformist Left expressed in Numax presenta… came at precisely the same time as in Spain leftist political parties (in particular the PCE/PSUC) and the trade union movement were negotiating their legalization, that is their incorporation into the orbit of the State and its institutions. In this sense, Numax presenta… is a political intervention in direct opposition to the political moment of its production that has left, in turn, a legacy that goes beyond mere historical anecdote. Numax presenta… is the story of those left out of political discourse, of those who have no voice in the historical process — the order of discourse — but who, irrespective of their status, act politically so as to give shape to their lives. Their struggle is within a tradition of workers taking control of production, indifferent to the connivance between union bureaucrats and management (from the shop floor to the national stage), from which they are excluded.

Autonomía obrera extends the idea of work beyond the factory walls. Or rather society becomes the factory, within which transformation is as much about individuals — notably questions of subjectivity and desire — as it is about institutional change or economic demands. While Numax presenta… coincides with and offers a commentary on the Transition, it also provides a rare critique of the dominant consensus of the time, at odds with what proved to be the outcome of the negotiations that would bring into existence what, following the mobilizations of the 15 May, 2011 [15M] movement, would come to be known as the Regime of 1978, and most significantly — for working class organization — it provides a rare example of a critique en directo of the “Pactos de Moncloa” at the very moment of their negotiation. The film thus marks a convergence of a historical moment with a contemporaneous local action at odds with that moment but also, like the 15M, it posits an alternative: the desire to change the way — the form — of life of its protagonists, to break with — via rejection and refusal — the grinding alienation of the factory and the assembly line even if self-management brought about a consciousness of the realities of capitalist production.

If Numax presenta… constitutes a critical intervention in the Transition, it is also a film that combines within its own structure different forms of representation: reenactment, theater, real archive footage material, photographs, newspaper clippings, and oral testimony. Representation is the key word here not only of cultural critique but also of the political moment. The word Transition, until recently discursively established within the Spanish state as synonymous with democracy, is just the most glaring example of the politics of representation. But within that discourse and simultaneous to the filming, class representation (the trade unions and the PCE/PSUC), the official doctrine of representation that remains in place today was being forged. The groundwork for monopolizing the definition of democratic discourse — an order that has been firmly policed ever since to the exclusion of the demos — was was being established.

The first two thirds of Numax presenta… is punctuated by staged sketches that Jordà shot with the assistance of theater director Mario Gas and his workshop actors that recount the history of the Numax factory (the dubious Nazi past of the company’s German owners who arrived in Catalonia in the aftermath of World War II, the asset stripping prior to their flight and decampment to Brazil, the ongoing dispute that commenced two years previous to the shoot, and the complicity of the official Left and the union bureaucracy with the process). Theater is a mode that has interested Jordà in later films too. The combination of the seemingly incompatible registers of theater and film contribute to the discordant tone. Clearly, an element of this involves Brechtian distanciation. There is an effort on Jordà’s part to correlate the alienation of factory work with that of cultural work, to unravel and expose its mechanics onscreen. This though, in turn, produces a seepage that unfolds to reveal other aspects of political and filmic practices. In a film whose initial — and expressed — intent was a collective enterprise, it is noteworthy that Jordà shot the staged commentary at his own initiative and without the assistance or participation of the Numax workers. Indeed, this points to a disruption of the theoretical paradigm in modern film theory that would suggest a theoretical tension arising from the de facto equality established between the collectivity and the film auteur.

That said, substantial sections (and arguably the film in its entirety) of Numax presenta… are also staged, but within the setting of the factory itself. The ostensibly naturalist style of filming contrasts with the evident artifice of the theater production. Shot in color (the factory sequences are mostly in black and white) the theatrical interjections within the diegesis draw attention to their fake quality (a belly dancer, a tightrope walker, a juggler, — the proscenium stage setting itself, the stilted text articulated in the mouths of the jobbing actors). Meanwhile the workplace ‘stagings’ are more ironic and integrated within the factory environment. Emblematic of this is when one of the workers is shot delivering a pre-prepared speech while framed within a cubicle. The camera slowly withdraws to reveal the man seated on a toilet, one of a line of identical stalls. As he finishes and stands to pull up his trousers, he rounds off his scatological diatribe with the commonplace: “una imagen vale más que mil palabras”/ “one image is worth more than a thousand words”. Sequences such as this one mirror the set of shots that introduce the film. A written text, establishing the background, the motives and the terms of the film as part of the collective project, read by a single worker in a medium shot that expands to incorporate a surrounding circle of applauding workers, followed in turn by a lengthy, looping tracking shot that opens up the space of the shop floor and the mass meeting of the occupiers, a shot that captures in its arc the machinery, the factory layout, the assembled self-managing workers. Both instances are stylistic components — formal elements — of the film as a whole: the factory dispute and the form by which it is articulated in filmic language. Both highlight, bring to the surface, the tension and the stress lines between the visual effect and the written text, the image and the word.

In the interview with Guerra, Jordà disavows the specificity of mise-en-scène in favor of what he calls narrative technique. In particular, in striking contrast to the worker Jordà films in the toilet cubicle, Jordà claims a disinterest in the image altogether. He claims he does not look through the camera viewfinder during the shoot, leaving questions of visual composition to the judgement of the operator and the cinematographer. Disingenuous though this may be (mise-en-scène — a term whose origins lie in theater — is fundamental to Jordà’s work), it does say something regarding the form of the essay, the essay film in particular and, indeed, form itself. Whatever else form is it is not immovable, it is flexible. Moreover, the traditional dichotomy between form and content proves (and, once more, this returns us to performativity) to be false. In an echo (albeit a contradictory one) of the worker’s sentiments, the antecedents of the essay form do indeed lie in the written word rather than in the image. But the essay is also the form of crisis, it is perhaps crisis writing itself. I will return to this point in the conclusion of this chapter.

If theater is important to the cinema of Jordà, it is also important to the thinking of Ranciére in his definition of politics, both in the literal and the metaphorical sense of the term. As I suggested in the very first paragraph of this chapter, the title of the film Numax, presenta… contains the suggestion of a performance. Rancière, meanwhile, conceives politics as organized in terms of a staging of the way power is perceived. While I do not wish to suggest any direct influence of Rancière on Jordà, the theatrical interludes contribute to this element of staging. What is often presented as fly-on-the-wall documentary (particularly in the case of the mass meetings or assemblies) transpires to be reenactment. This is more explicitly the case when the workers recollect the beginnings of the dispute: the first meetings, the roughing-up of one of the managers, the breaking of an office window in one of the protests, the alternation between the direct testimony and its fictional recreation. But it is also there at the very end of the film, precisely when we are most led to believe in its naturalism. In the final sequence, the only one in which Jordà himself — a self-parodic signature — appears (though we occasionally hear his voice asking questions earlier), the workers celebrate the end of the occupation. A group of workers form the band that performs the music that accompanies the farewell bash, notably the tango Adios muchachos, popularized by Carlos Gardel. Jordà, meanwhile circulates, microphone in hand, and interrogates the workers as to their future plans. Someone shouts out the question “¿Qué opinas de Lamas?”/“What do you think Lamas?” (Lamas being the supervisor who had earlier been beaten by the female workers). In jocular fashion, one of the older men assumes the role of Lamas and the women slap him around. Within the representation, at the very moment when the film displays its apparatus, that is, when it is at is most Godardian (with the presence of Jordà, armed with the filmmaking sound apparatus, conducting interviews), the workers themselves re-represent, they act out, an instant of their own narrative, a narrative that exemplifies its politics of refusal in its refutation of the dominant idea of the Transition as model, as peaceful and consensual.

That this should come in the final sequence of the film is significant. The film is bookended (in two sequences that are marked out by being shot in color) and given form precisely by the kind of performativity I mentioned at the beginning of the chapter; it is brought into being, instituted or constituted by it at the very moment when a new state is being born under the auspices of a Constitution. Numax presenta… thus functions as an antagonistic alternative to the official historical narrative, but this is characterized by the absorption of the film’s thematic substance into its form. The traditional binary collapses and the two critical dichotomous terms become indistinguishable precisely at a moment in conflict with the conjuncture. While the film is marked by a style that reflects both the concept of collectivity: the workers (who financed the film) and the act of speaking for themselves, it also gives performativity a sense that links the theatrical notion of performance to the linguistic version. The first sequence — the reading of a written text (an essay within an essay) — is a declaration of intentions and it is one that poses a challenge to the institution of film itself; it institutes a counterinstitution, one that vies with the parodic narrative of professional actors provided by Mario Gas’s troupe on an actual stage.

In the age of neoliberalism the words democracy and demos from which it derives have taken on particular formal connotations. One of the interesting things about Numax presenta… is the year it was shot — 1979 — coincides with the arrival on the world stage of neoliberalism as a dominant discursive political and cultural formation. The scenario of the demos, a word much deployed nearly thirty years later, is the disputed stage upon which the struggle of the film is acted out. Demos, the domain of the excluded, what Rancière calls “the part that has no part” (Dissensus 70) — literally and metaphorically frames the film. The complications of autonomous production under capitalism, self-organization, self-governance, and control, not only of ‘the means of production’ but also over one’s life, are the themes of the discussions staged throughout the film. In direct contrast to the parallel negotiations regarding and, more to the point, defining the limits of democracy that were taking place at the same time in Madrid. Thus, the formal organization of the film — its central trope which gives voice to the hitherto voiceless — corresponds to the wider antagonisms, their discourses and definitions, debated beyond the frame of the screen. This too makes the film a political — militant — intervention, an event.

In spite of Jordà’s disavowal style is an important feature of Numax presenta… The use of color in the introductory and final sequences of the film denotes actuality, the now of the conflict and the film itself, their common coincidence in time at the beginning and end of the film, in contrast with the repetition and recreation of the dispute itself (almost — though not quite — in sepia-style). Given the use of color to shoot the theatrical episodes, a sense of disruption to the form itself develops; a disruption, moreover, that is historicized by the formal innovation.

Transformation in social forms, meanwhile, is what exercised — and continue to exercise — the autonomists, in their endeavors to take the struggle of the factory to the wider world beyond. Filmic, historical, political, and social forms are marked by limits and barriers to which disciplinary concerns subject them in the same way as aesthetic forms. There is a transference inherent in the idea of transformation. The placing of Numax within the city of Barcelona is realized filmically by the shots of the hazy silhouette of the Sagrada Familia — emblematic of the Barcelona skyline — against which the group of women workers discuss the situation as they smoke on the roof or the terrace of the factory. Form is of course many things that work within and without the text: tropes, figures, genres, among them. Numax presenta… is part of the factory film genre, its essay form, a mode of filmmaking that Jordà specialized in throughout his career. Prior to embarking on his Communist Party-sponsored projects, the director had made what is arguably a performative essay in which Catalan writer Maria Aurèlia Capmany discusses her novel Un lloc enter els morts. Jordà’s essays are defined by filmic speech acts that challenge the traditional separation of form from content. At the same time they historicize form; text and context entwine, align, and integrate with each other.

Veinte años no es nada (2004)

Jordà’s question to the Numax workers regarding their future at the party with which the film culminates is met with a unanimous refusal to contemplate a future devoted to salaried labor and assembly-line factory work: in what is paradigmatic of the autonomists rejection of work gives rise to a dissensus.

Twenty-five years after Numax presenta… Jordà, as if in response to the open-ended coda appended to the title of the earlier film, and so as to provide concrete answers to his original question, sought out the protagonists of the earlier film and persuaded them to participate in a second production. The relation between the historical moment and the filmic diegesis in Numax presenta… is marked by a concentrated, saturated and complex set of contradictions that bind and hold in abeyance the collective and the conjuncture. Veinte años no es nada, on the other hand, is about the dispersal and the consequential singularity of each individual experience. While the collective has evaporated, in the previous film’s logic of reenactment, the staged reunion of 20 años no es nada carves out a return. Although there is no theatrical narration, it is clear that many of the encounters are set up for the purposes of the film. The very evident differences in the filmic compositions of Numax presenta… and Veinte años no es nada, wittingly or not, have a relation (if not exactly a correspondence) with the shifts in the political forms that the passage of time has wrought. The point is important. Dissensus and dispersal raise formal questions too. At the heart of the displacement is a paradox: a contradictory condensation.

Once more while these films are not reducible to the conjuncture alone, there is a relation between their on-screen interiority and the off-screen exteriority. Just as Numax presenta… has a discordant relation to its historical moment that prompts its internal debate, so too 20 años no es nada is highly conscious of its place in relation to the broader world. These films though are not allegories of their respective periods. Their exemplary quality is as exceptions, they are allusive symptoms of their times rather than metaphors. They are films that, in their very different ways, give voice to the unheard, those excluded from dominant discourse; to recall Rancière, the part that has no part.

If the first film was inspired by the collective experience (almost nobody is identified, except by their first names and in passing, even in the credits of the film), the focus of the second, two and a half decades later, is on the stories of the individuals. The shift of subjectivities is a notably distinguishing factor between the two pieces. Names, in this second film, are used throughout. The traditional notion of the working class as concentrated in one place is dislocated; mobility and individualization prove the characteristics of 20 años no es nada. The common experience shared by the individuals now atomized points to a new and different sense of crisis, a crisis of collective action. The point however is how such abstraction — the relation between time, and individual/collective experience — might be filmed. Although there is no repetition of the theatrical commentary of Numax presenta… the entirety of Veinte años no es nada is in a sense staged, corseted within the parameters of its predecessor. The film establishes a scenography. As well as being a film about the evolution of a group of once-militant workers, it is a film about a film, a metafilm. Numax presenta… is screened during the reunion dinner of Veinte años no es nada. The condition of filmmaking itself — its essayistic quality — is wrapped within the interrogation of the concept of political militancy in the era of neoliberalism. As Jordà’s final film (he would die in 2006), it also brings to an end the director’s trajectory as a militant filmmaker; it points to a conclusion of sorts, a drawing together of life and representation in a very personal expression of biopolitics.

There is though an element that disrupts — a further dislocation — any tidy, sentimental ending: the demos, that which has been left out of discourse, the remainder, not only of that which is rendered surplus to needs but discounted altogether, excluded from the count, off sets succinct calculation. The labor market itself in these two and half decades between the two films has changed dramatically. By 2004 many of the benefits for workers of the Moncloa Pacts, for which the representatives of the working-class movement had willingly sacrificed their labor power in exchange for benefits — most notably stable employment, job security — had been whittled away in the name of corporate exigency. Unemployment had rocketed and created an army of alternative labor that threatened the conditions and security of salaried workers. Though never articulated as such the discourse of precariousness is characteristic of the post-1979 period. Meanwhile, autonomism emphasizes creative resistance, self-education, and re-education. It is about reclaiming the time that would otherwise be given up to work for oneself. If the initial project of Numax presenta… concerned the crises prompted by collective self management, Veinte años no es nada is about what each of the protagonists subsequently went on to make of their own lives; much of which deals with new and different forms of waging the struggle that Numax initiated. Autonomism concerns refusal, it is about refusing to conform to the discipline — the bodily discipline — imposed by the rules of everyday life, a rejection of temporal and spatial order, symbolized by the regulatory conditions of the daily routine of factory work. Discipline has extended to the world beyond the factory walls and even beyond the frontiers of the human body. Paradoxically though — and herein lies the nub of the film, the contradiction at its center — Veinte años no es nada is also a film about losing the collective spirit. Indeed, a significant part of the film focusses on individuals who now work, if not exactly for themselves, alone (the taxi driver, the artisan, the school teacher, the owner of a bar, the sales rep). Precariousness, given material form in the uncertain future contained in the title of Numax presenta… , is what distinguishes the labor market of 2004 but it also characterizes other aspects of life, such as housing and affective relations. The body is more fragile. We get a sense of this early on in the film when Emilia, a woman who heralds from León (and who says “Cataluña ha sido como una universidad”/“Catalonia has been like a university”.). Now she runs a bar which, after many years, she is in danger of losing owing to speculation and gentrification. Meanwhile, another former Numax employee, Blanca, works as an elementary schoolteacher of evidently underprivileged, marginalized children in Cordoba. Blanca’s charges and Emilia’s situation point to a shift in historical temporality governed by new uncertainties.

Time enfolds in this second film; the apertures in its creases are revealed by promiscuous plundering of archive material, of memories, and testimonial. Time also reveals the presence and the uneven shifts, the new forms of protest and new subjects of resistance. Veinte años no es nada was released at a significant historical juncture. While not as emblematic as 1979, 2004 is also a watershed year. Arguably it is the year when the street and the public square become singular sites of struggle. It is the moment of the anti-globalization movement and when popular mobilization first pose a serious threat to the institutions of 1978 in Spain. 2004 is the year in which the demos took center stage of political struggle and began to effect real change. The year prior to the making of the film was marked by what is arguably the world’s largest ever mass mobilization in opposition to the second Gulf war. In Spain the ¡No a la guerra: otro mundo es posible! moment (that had developed out of the anti-globalization movement, itself a response to neoliberalism) had momentous effects. A year after the US-led invasion, the Aznar government was brought down following the exposure of its deception following the commuter train bombings by Islamic militants on March 11, 2004 during the general election campaign. This led to protests outside the headquarters of the ruling party and a sudden reverse in the predicted vote. Veinte años no es nada was of course made quite independently and prior to these events — the fact it emerged in the same year is coincidence and no mention is made of them in the film — but in light of the politics of the two films, it is perhaps relevant. This is particularly so given that the anti-globalization movement is arguably heir to Autonomía, with which Jordà had once been associated.

The interim between the first film and the second sees a world transformed unimaginably for the participants in both pieces. The Cold War has ended, neoliberalism, whose symptoms were signaled by Foucault in 1979, has seemingly triumphed. If Numax presenta… turned on the collective experience, Veinte años no es nada’s focus on the life stories of the individuals gives rise to a tension here between the autonomist refusal of the factory model and the neoliberal conceptualization of the individual. Carlos, who features in the final moments of the earlier film and who now works as a taxi driver in the streets of Barcelona captures this ambiguous change in conversation with two of his erstwhile workmates: “Hay mucha individualización,”/“There is a lot of individualization”, he says, lamenting the contemporaneous absence of solidarity that his generation experienced in the late-1970s. The desire for “una forma de vida diferente”, “a different way of life”, to cite one of the women who formerly worked at Numax. The irony regarding the formation of political subjectivity is pointedly made in the respective soundtracks: while the first film ends with a tango, the second culminates with a screening of the original film followed by a collective rendition of the Internationale.

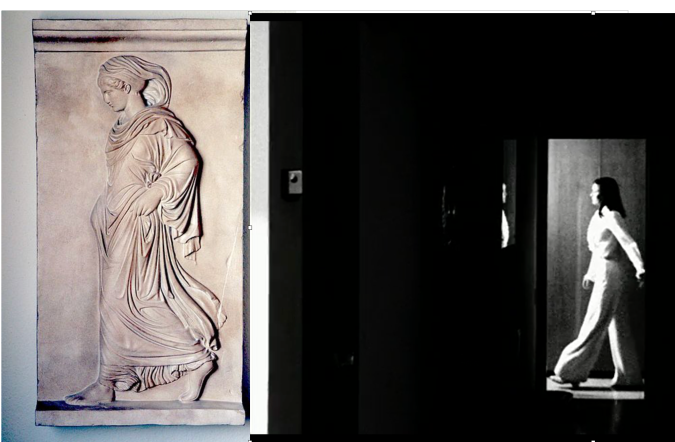

Reminders abound of the social factory beyond the confines of the old traditional Fordist model of industry. If in the first, the Sagrada Familia appears shrouded in cloud, its grey outline providing the backdrop to the ongoing debate filmed in black and white, in the second it is shot in glorious color as Carlos the taxi driver, points it out to his Italian clients. Tourism, always important to the national economy, has replaced manufacturing. The city and color provide the visual signs of changing times but, as the singing of the Internationale suggests, Veinte años no es nada also has a particular soundscape Sound, music, and speech are key elements of both films. The tango of the first film is countered in the second with another Gardel tango Volver (“Return”), giving its title a double meaning: the passage of time and a return to the past. Title aside tango is a genre tinged with affect, with desire, loss, and pain; the affective inflections of biopolitics. There is an aspect of oral history in the second film, while verbal debate is at the heart of the first. If, as I suggested earlier, the camera captures those voices, there are other implications too. The reunion takes place in a Barcelona restaurant and one of the first people introduced is the deaf-mute son of one of the workers, now dead, who participated in the original dispute. There is a hint here of Plato’s Phaedrus, when Socrates distinguishes between the writing and speech: “they have no parent to protect them; and they cannot protect or defend themselves”. While clearly the philosophical point is different, it is striking that the figure here is both an “orphan” and he is a figure who lacks the power of speech. We might read into this a somewhat different configuration: film qua writing, the mute orphan as demos. This idea might be reinforced by another example. A yawning absence in the film is that of Juan Manzanares. A silent figure who died prematurely of liver disease, he is represented in the film by his loquacious former lawyer. One of the interesting features, given the previous reference to Plato and my reading of the presence of the mute boy, is that the interview with the lawyer provides the sole occasion in Veinte años no es nada for Jordà himself to appear on screen.

In a film about legacy, a film constructed around testimony, the figure of the deaf mute heir to the class struggle is charged with symbolic and affective power: he is in a sense an exemplary case of the (literally) voiceless, the demos that is the focus of Ranciére’s work. Amid the sonorous and auditory continuum in the film (and in many ways both films are oral and musical accounts) he represents a silence, a void or gap in the discursive narrative, a certain formal autonomy or supplement in the absence of his deceased father. In an affective gesture that exceeds the confines of the body, as the screening of Numax presenta… comes to an end, he wipes away the tears rolling down his cheeks as if the whale bones that line the confines of the metafilm had failed to fully contain its interior content within its corporeal limits. It is perhaps significant that Carlos, the taxi driver who a quarter of a century earlier at the party that marked the end of the occupation of the Numax factory and the film played drums and thus maintained the regulatory beat of the musical arrangement, tapping out the rhythm of an alternative order. It is apt then that he now passes the time when he is without passengers interacting with language tapes. Not only an autonomist use of working hours for his own benefit but a technological self-education in oral expression.

While individualizing what was a collective struggle the film centers upon questions of affect. Juan Manzanares is spoken of with greater dignity and understanding by his partner Pepi (Josefa Sánchez), one of the more vocal participants in the film of the original dispute, than by his lawyer. A key figure whose story occupies a significant proportion of this second film, — she now runs a shop in Barcelona selling her own artisan products— she and others took up arms in the aftermath of Numax and held up banks at gunpoint to sustain their militancy. Pepi talks movingly about Juan, his life and his death, “era muy humana, extremadamente humana, muy sensible” “He was very humane, extremely humane, very sensitive”. We learn from television archive material the story of Juan’s final robbery in 1985 of a branch of the Banco de Sabadell in Valls, in which Pepi did not participate. Manzanares took the employees hostage, demanded the presence of the then Minister of the Interior, José Barrionuevo, and shot and seriously wounded the then Civil Governor of the Tarragona province, Vicente Valero, who entered the bank in representation of Barrionuevo, as a supplement and a substitute. There is an interesting correlation here with the artifice of the theatrical stage reenactments of history in Numax presenta… . Providing an interestingly skewed perspective on cultural memory; the footage from the television archives’ report embedded within the filmic text of Veinte años no es nada posits two immediacies, two nows, two present moments, as events viewed (by us, the spectators) in hindsight. The now indexed by the sequences shot in color of the initial and final sequences of Numax presenta… is echoed (with concomitant distance or remove) here. The immediacy of the figure of the direct witness of the 1979 film is articulated through reminiscence, by the rhetoric of defeat, in a register of melancholia condensed in the collective singing of the Internationale.

Demos refers to the uncounted or the un-recounted, that which has been left out of written accounts of history, that has been institutionally muted and not permitted a voice of its own. A trace though remains in the spoken word, this condition of oral testimony, in the fragments of memory that provide another kind of legacy unrepresented in statistics or official narratives. The voiceless demos is, in this sense, empowered by such an inheritance. The performative quality of the lived remembrance of the witnesses themselves is there in the conscious act of disputing versions of memory that by 2004 had become one of the dominant academic and political discourses in Spain. Veinte anos no es nada ends with an intriguing image of inheritance and legacy. While in 1979 Jordà had asked the Numax workers as to their future plans, in 2004 he does not have the same opportunity. The final shot of the film frames a child of around three, apparently Carlos’s young daughter, her doll in one hand, the fist of the other raised, while the collective, their backs turned to her, sing the revolutionary hymn. Seemingly overdetermined, clichéd, even perhaps opportunistically staged; it is an image of the militant future, of struggles yet to come.

Conclusion: the essay as the form of/for crisis

This rather forced ending, theatrically set up as a reaffirmation, is the visual image, the incarnation, of the open-ended “…” that hangs off the end of the title of Numax presenta… , the pending, ongoing and future resistance in a different configuration. Earlier I cited filmic texts set in the factory set very much apart from one another and, in turn, from Jordà’s films by time. Both the Fassbinder TV series and the Portuguese The Nothing Factory are fictions, Jordà’s films are — in theory at least — documentaries. The way they broaden to incorporate fictional strategies facilitates the undoing of film’s claim to naturalism, they provoke a rupture, formal ruptures of the conventions of fiction and non-fiction, or that suggested by Jordà himself between word and image; they enact crisis. The cinematic essay is the form of crisis that, in turn, generates something unassimilable — like the demos itself — an excess or supplement within critical practice itself. The crisis the essay form aptly responds to is political crisis, not as a passive correlation but as active intervention, as subjective participant in an act of resistance. In this refusal there is a performativity that links protest with theatricality.

For anyone who has been involved in grassroots politics in Spain over the last two decades, it is a strange and slightly unnerving sight to see video artist and activist Marcelo Expósito presiding over that most theatrical of stages and the most institutional of institutions, the Spanish Congress. However, as — prior to the Spanish general election of April 28, 2019 — fourth in the hierarchical chain of house speakers and member of parliament for the formation “En Comú Podem” this has indeed happened in recent years. ‘En Comú Podem’ — the Catalan sister organization of Podemos — is very much part and product of the 15M movement and the mass mobilizations of 2011 that saw the central squares of almost all of the cities of the Spanish state occupied by protesters.

In 2004, the same year as Veinte años no es nada, Expósito, based (if not born) in Barcelona, released an hour-long video essay that exemplifies the kind of formal filmic engagement with politics that this chapter has sought to demonstrate in Jordà’s work. Expósito depicts the evolution and operation of the social factory, and does so by focusing directly on the work of one of the original autonomists, Paulo Virno (who appears in the film). Primero de Mayo (la ciudad-fábrica) was shot largely in the city of Turin, at the site of one of Fiat’s most emblematic factories now transformed into a commercial center. Former factory workers and immigrants, recruited as private police, battle against their excluded cohorts, the unemployed, music techies, wifi geeks, punks, situationists, and other cast-outs from society who seek to resist the speculators. This staging of the demos is a sign of neoliberalism’s brutal conquest of space and the resistance to it, the antiglobalization movement that in time would give rise to the world-wide revolts of 2011. Gerald Raunig describes Primero de Mayo (la ciudad-fábrica) in the following terms reminiscent of the apparent shift that has taken place between Numax presenta… and Veinte años no es nada:

“Marcelo Expósito’s video… outlines a complex introduction to the shift from

the Fordist paradigm of the factory to the post-Fordist paradigm of virtuosic cognitive

and affective labor. He takes as his model the Fiat factory Lingotto, a proud center of

automobile production in the 1930s and now—having been transformed into a

multifunctional hotel and conference center—a hotbed of the service industry and an

example of the fabbrica diffusa. (The operaist term refers to the factory that has been

diffused into the city, into the private spheres, into the forms of life.).”

With this in mind, I want to conclude with reference to what Laura Rascaroli has called “the potentiality of all essay films to question and challenge their own form” (300). It is the essay as the critically shaping subject productive of its own subject matter via the performance of commitment, that points to a continuation of the militant tradition of filmmaking (of which Expósito is only one of Jordà’s heirs). In the same volume as Rascaroli, Elizabeth Pazian and Caroline Eades, describe the essay form as “dialectical thought that gravitates towards crisis. Thus it fosters the development of new forms”. There is within and between these two films a temporal dialogue and dialectic between enactment and reenactment, between chronology and anachronology, a spectral relation between the militant event and its representation. That the two films discussed here focus on crisis (the collective crisis of the Numax dispute and the individual crises of its participants decades later) at two different moments of political crisis whose effects endure suggests a convergence that exceeds anecdotal coincidence, one that points to an openness to future political change and the filmic response to it.

Works cited

Díaz Valcárcel, José Antonio and Santiago López Petit, El discreto encanto de la política. Crítica de izquierda autoritaria 1967-1974. Ruedo ibérico. Edición especial 40 años. Editorial Icaria, Barcelona, 2016

Garcés, Marina, ‘Numax, nuestra universidad. Conversación con Joaquim Jordà’, Revista Zehar nª58, Donosti (2006). 10-13.

Guerra, Carles, ‘La militancia biopolítica de Joaquín Jordá : The Biopolitical militancy of Joaquín Jordá’, Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema · Vol. II · Núm 5. · 2014 · 50-55

– – N for Negri: Antonio Negri in Conversation with Carles Guerra. Grey Room, No. 11 (Spring, 2003), pp. 86-109.

Hallward, Peter, ‘Staging Equality: Rancière’s Theatocracy’, New Left Review 37 January-February 2006. 109-129.

Jordà, Joaquim, ‘Numax presenta … y otras cosas’ , Nosferatu, Revista de cine. 9. 1992. pp. 56-59.

Pazian, Elizabeth A. and Caroline Eades (eds), The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia (London and New York, Wallflower Press). 2016.

Rancière, Jacques, Dissensus (London: Continuum), 2010.

– – -‘The Thinking of Dissensus: Politics and Aesthetics’, in Reading Rancière. Paul Bowman and Richard Stamp (eds) (London: Continuum), 2011. pp. 1-17.

Raunig, Gerard, ‘Modifying the Grammar. Paolo Virno’s Works on Virtuosity and Exodus’, Art Forum, January 2008.

This is the text of a paper I delivered here at UIC in Chicago last Friday as part of our ongoing encounters on “Critical Theory, Psychoanalysis and the Politics of the Archive in Spanish Cinema”.

This is the text of a paper I delivered here at UIC in Chicago last Friday as part of our ongoing encounters on “Critical Theory, Psychoanalysis and the Politics of the Archive in Spanish Cinema”.